On a hot day in May, Andrew L. Smith Sr., a vegetable farmer from Ludowici, Ga., listened with skepticism as Tom Vilsack, the U.S. agriculture secretary, touted President Biden’s efforts to help Black farmers overcome decades of discrimination.

Seated alongside hundreds of farmers in front of a former plantation once owned by a Georgia slaveholder, Mr. Smith, 62, wondered why he had not benefited from any of those programs, including one aimed at helping Black farmers clear their debts.

Mr. Smith, a third-generation farmer, said he was especially frustrated that he is not eligible for another effort that will compensate farmers who have faced discrimination. He was told that he cannot apply for that money because he does not have the correct paperwork documenting the discrimination his family faced.

“We march on using what we got and then they tell us that you can’t even use that,” he said.

Mr. Smith voted for Mr. Biden in 2020. This year, he is considering backing former President Donald J. Trump.

Black voters are key to Mr. Biden’s re-election, but many say they are disenchanted with the president and are considering voting for Mr. Trump in November. The visit by Mr. Vilsack to the Sherrod Institute’s annual “field day” in Albany, Ga., was part of an intensifying effort by Mr. Biden’s top aides to court them ahead of the election. Polls show that Mr. Biden’s support among a constituency that powered him to victory in 2020 has been shaky in critical swing states like Georgia, where Black farmers are a small but important voting bloc that is feeling let down.

At the farm event, Mr. Vilsack tried to make the case that progress is underway. He pointed to a new racial equity committee, the hiring of several Black leaders and efforts to root out racism within the Agriculture Department, which some Black farmers call the “last plantation” because of its history of lending policies that discriminated against Black farmers.

“It’s been an uphill battle,” Mr. Vilsack said of the plight of Black farmers in America. “An act of defiance against the system designed to protect the incumbent.”

The overture was met with polite applause but also with doubts, echoing the sentiments expressed by Black farmers both in Georgia and nationwide during Mr. Biden’s term.

Relief Hopes Raised and Dashed

When Democrats passed the 2021 American Rescue Plan, it included $4 billion of debt forgiveness for Black and other “socially disadvantaged” farmers, a group that has endured decades of discrimination from banks and the federal government. The agency sent out letters to approximately 16,000 farmers around the country about the coming awards, stoking hope that financial relief was on the way.

One of those letters was sent to Paul Copeland, a farmer in Shiloh, Ga., who received an official notice in 2021 that the loan on his property would be forgiven. Mr. Copeland, who has about $150,000 left to repay, said he planned to invest in his ranch, where he raises about 70 cows that he sells for beef, once that financial burden was lifted.

But the promise of the debt relief program was dashed after groups representing white farmers filed lawsuits to block it, arguing that the federal government was engaging in reverse discrimination by awarding money based on race. The lawsuits were initiated by America First Legal, an organization led by Stephen Miller, a former top Trump administration official. The Department of Justice ultimately declined to appeal a court ruling that blocked the program from going into effect.

Mr. Copeland, 65, has kept the letter. “It’s a reminder of what I could have done, a reminder of a promise not fulfilled,” he said.

Democrats tried again in 2022 by creating two new funds to help farmers as part of the Inflation Reduction Act. There is a $2.2 billion program to provide financial assistance to farmers, ranchers and forest landowners who faced discrimination before 2021. And a $3.1 billion program to cover loan payments for farmers facing financial distress.

The financial distress program has paid more than $2 billion to more than 40,000 people, and the Agriculture Department estimates that Black and “underserved” farmers have benefited the most.

However, the fund for farmers who have faced discrimination, which could include any ethnic group, has yet to pay out anything. The U.S.D.A. has employed outside firms to vet more than 60,000 applications. The money is expected to start flowing in August.

To some Black farmers, the balky process is reminiscent of their experiences when trying to get settlement money following racial discrimination lawsuits in the 1990s.

“The very agency that did the discrimination is rolling out the program and determining what’s going to be,” said John Boyd Jr., the president of the National Black Farmers Association, which has been helping its members across the country navigate the application process.

Mr. Boyd sued the federal government in 2022 for failing to follow through on the original debt relief program. In May, he visited the White House to press for debt forgiveness and a foreclosure moratorium for Black farmers across the country.

The lack of progress has convinced Mr. Boyd that he cannot support Mr. Biden’s re-election bid. While he did not say that he was ready to back Mr. Trump, he suggested that the Trump administration had worked harder to help white farmers than Mr. Biden had for Black farmers.

“Those farmers who have Trump signs in their yard, Trump made sure they got some happy checks,” Mr. Boyd said, referring to more than $20 billion in payments that Mr. Trump made to compensate farmers for lost sales as a result of his trade war.

A federal watchdog report showed that most of the aid went to large farms, which are predominantly white-owned.

“Here I am fighting with an administration that should be embracing our population,” said Mr. Boyd, who did receive a few thousand dollars of aid money during the Trump administration.

Shrinking in Size but Growing in Political Clout

The fact that Mr. Biden has fallen out of favor with a key voting bloc underscores the significant challenge he faces in the fall.

A New York Times/Siena poll in May showed Mr. Biden trailing Mr. Trump in Georgia by 10 points, with 20 percent of Black voters leaning toward backing the former Republican president in a two-way race. While Black farmers are a small slice of the population, their vote could be critical in a state that Mr. Biden won by just 12,000 votes in 2020.

Black farmers have been shrinking in numbers amid economic obstacles and difficulty getting loans. They have lost about 90 percent of their land over the last century as large agricultural corporations have become dominant and consolidated the nation’s farmland. By 2022, the 42,000 Black farmers left in the U.S. represented about just over 1 percent of the nation’s 3.4 million farm operators.

Some are threatening to make their voices heard at the polls.

In January, Corey Lea, a Tennessee cattle rancher and director of an organization representing rural Black America called the Cowtown Foundation, sent a scathing letter to Mr. Biden and top Democrats stating that Black voters, particularly farmers, “shall denounce unwavering support of the Democratic Party.”

Mr. Lea, an Independent voter who is suing the Biden administration over its relief programs, has been raising money on his website to “defeat Joe Biden” in 2024. He took his message to Atlanta in February and told an audience at the Georgia Black Republican Council that America’s Black farmers and ranchers had seen very little monetary support from the Biden administration. He reminded them: “There is power in our vote.”

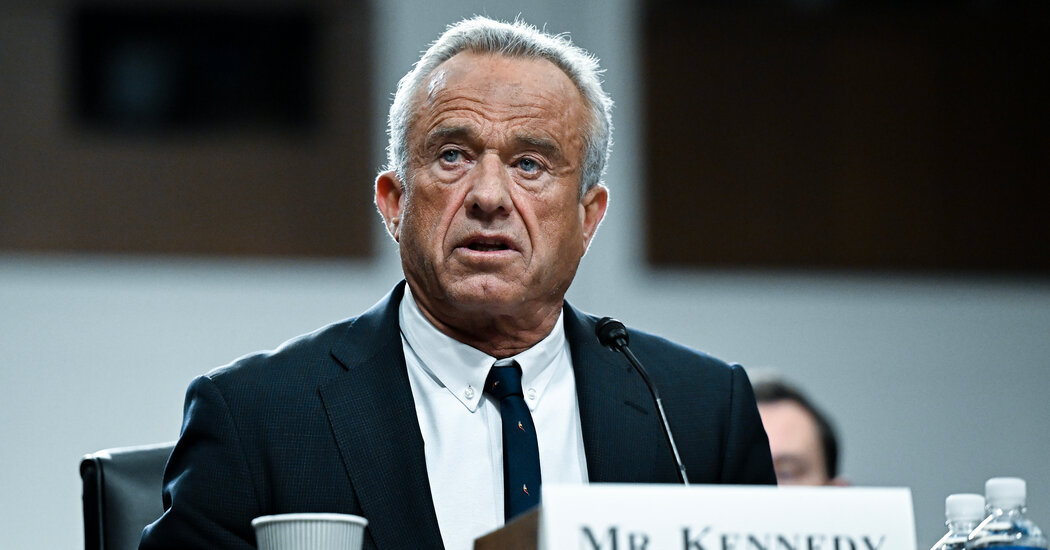

Other candidates are trying to capture that vote. Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the Independent candidate, said in May that if elected he would remove the Agriculture Department’s leadership and give Black farmers the money that had been “stolen” from them.

Allies of Mr. Trump have been targeting Black voters in rural Georgia. The Make America Great Again PAC aired an advertisement nearly 1,000 times in Macon, Ga., from late April to mid-May, according to the ad tracking firm CMAG, blaring headlines about Black and Hispanic voters abandoning Mr. Biden.

Janiyah Thomas, the Trump campaign’s director of Black media, said Black farmers are struggling under the Biden administration’s regulations and would be better served by Mr. Trump.

“With President Trump back in the White House, Black farmers will be able to feed the world without overreach by the federal government,” Ms. Thomas said.

A Frustrating Game of Waiting

John Slaughter, a 39-year-old Black farmer who owns 200 acres of land in Buena Vista, Ga., plans to vote for Mr. Trump in November. He believes that Democrats merely talk a good game when it comes to saying they want to help Black farmers.

During 5 a.m. prayer group meetings, Mr. Slaughter said that he and other farmers talk about the discrimination they have faced and wonder about their relief money applications. In many instances, farmers have lost the deeds to their farms after falling behind on payments or can only pay interest on their loans.

Mr. Slaughter’s farm is not currently operating, but he hopes to use any federal money to buy new equipment to get it up and running. He prefers Mr. Trump because in 2019 the Trump administration helped him resolve an administrative error that allowed his family to reclaim the deed for the farm, which once grew butter beans, purple hull peas and okra.

“I think we did better under President Trump,” said Mr. Slaughter, who traveled to Washington as a child with his father to protest discrimination against farmers. “President Trump, he did something for us while he was in office. President Biden, what have you done for me?”

A Push for Progress

Some prominent figures advocating the cause of Black farmers praised the Biden administration’s efforts to help them.

Shirley Sherrod, a former U.S.D.A. employee who advises the agency on racial equity issues and leads the institute that hosted the farm event, said that she is seeing signs of progress, such as more Black farmers being approved for loans. Ms. Sherrod, whose father was killed by a White farmer in the 1960s, said she did not think Mr. Trump would be better for Black farmers.

“What does Trump care about civil rights?” she asked.

Mr. Vilsack defended his agency’s work during an interview and said the Biden administration had faced stiff resistance when attempting to provide debt relief in 2021.

“We were faced with 13 separate lawsuits run by Stephen Miller and his ilk,” Mr. Vilsack said.

He also expressed frustration that legal and administrative obstacles had led to Black farmers being disappointed.

“You’d love to be able to write the checks immediately, but you can’t,” he said.