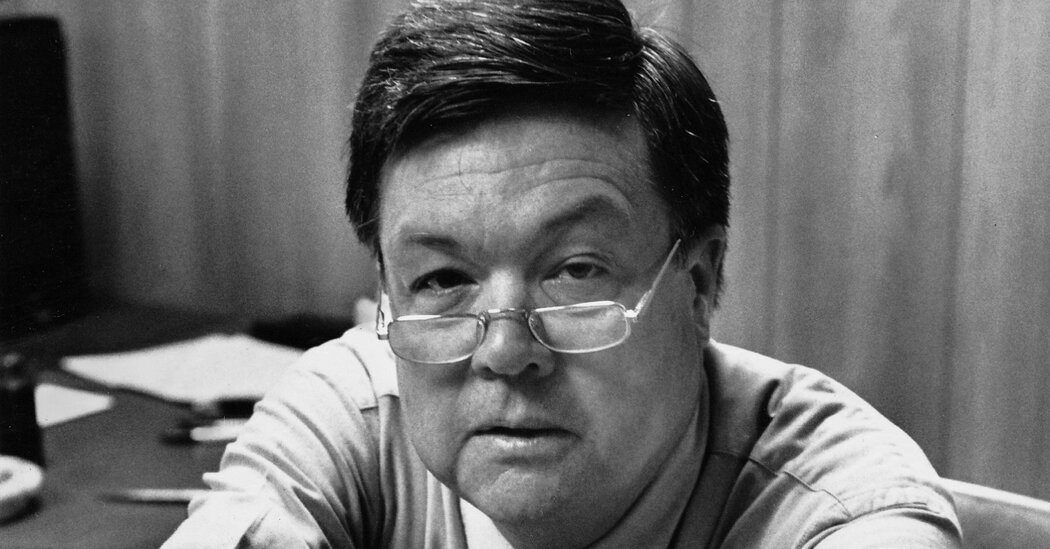

Denny Walsh, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter who was a consummate nuisance to mobsters, corrupt politicians and his editors, especially at The New York Times, which fired him, died on March 29 at his home in Antelope, Calif., a suburb of Sacramento. He was 88.

His daughter, Colleen Bartow, confirmed the death. She said he had been suffering from several respiratory ailments.

Mr. Walsh began his career in 1961 at The St. Louis Globe-Democrat, where he hot-dogged around the newsroom smoking cigars and used the floor as his ashtray.

“Walsh had the tenacity of a pit bull and seemed to be developing some of the facial features of the breed,” Pat Buchanan, the conservative commentator who was then an editorial writer at the paper, wrote in his autobiography, “Right from the Beginning” (1988). “His laugh was loud and uncontrolled and bordered on the malicious.”

Mr. Buchanan added, “When Walsh sank his teeth into a politician, he usually did serious damage, and he was always reluctant to let go.”

Investigative reporters are an idiosyncratic breed of journalist. Typically fearless, they are often a source of angina to their editors. Mr. Walsh was no exception. He liked to boast that he was sued multiple times for libel but had never lost a case. He was often at loggerheads with his bosses.

In 1969, Mr. Walsh and Albert L. Delugach won the Pulitzer Prize for local investigative reporting for a series of articles exposing fraud and corruption within the St. Louis Steamfitters Union, Local 562.

The next year, Mr. Walsh wrote an article that claimed Alfonso J. Cervantes, the St. Louis mayor, had ties to local underworld figures. G. Duncan Bauman, the newspaper’s publisher, killed the article, later explaining that he had called his own sources, who, he said, didn’t think the story was accurate.

Incensed, Mr. Walsh later publicly accused the publisher of having his own unsavory community connections. He quit and joined Life magazine, which had recently formed an investigative reporting unit. He expanded his reporting on Mayor Cervantes in a story that relied heavily on unnamed federal law enforcement sources.

Mr. Cervantes sued Life and Mr. Walsh in federal court for libel, arguing that the reporter had acted with malice and should be ordered to reveal his sources. A district judge ruled in favor of the journalists.

The case eventually landed in the United States Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit, which upheld the lower court ruling against the mayor. Mr. Walsh had not acted with malice, the court said, and the mayor had not “produced a scintilla of proof supportive of a finding that either defendant in fact entertained serious doubts about the truth of a single sentence in the article.” The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

Mr. Walsh joined the Washington bureau of The Times in 1973, at the height of the Watergate scandal — a story that the Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein had been dominating. The Times assigned Seymour Hersh, a reporter in the bureau who had won a Pulitzer for exposing the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War, to help the paper catch up.

“I’m scrambling around writing odds and ends, but Woodward and Bernstein were so far ahead, and I didn’t really know anyone in the White House,” Mr. Hersh said in an interview. “And then Denny shows up, this big husky guy, always chewing on a cigar.” (Newsroom smoking was by then a no-no.)

Mr. Walsh wasn’t interested in Watergate; he wanted to continue reporting on the nexus between politicians and the criminal underworld. He offered to connect Mr. Hersh to a source who might be of assistance on Watergate. “It was somebody in the middle of everything,” Mr. Hersh said. “And I suddenly had what you need — somebody inside.”

Mr. Walsh turned his attention to Joseph Alioto, the mayor of San Francisco. Look magazine had recently run a cover story that accused him of having multiple mafia connections. Mr. Alioto sued the magazine for libel and won. Mr. Walsh’s sources, however, told him another version of events — that the mayor had lied during his testimony in the case.

After holing up in a San Francisco hotel for three months to investigate, Mr. Walsh filed a lengthy story on the matter. A hullabaloo followed.

A.M. Rosenthal, the top editor of The Times, refused to publish the article. According to letters and memos in a collection of his papers at the New York Public Library, he didn’t think the piece materially advanced the Look magazine story.

Mr. Walsh was apoplectic. So was Mr. Hersh. “After some discussion about the quality of the piece and it’s publishability,” Mr. Walsh wrote in a letter to Mr. Rosenthal, “I asked Hersh if he had any suggestions as to who might be interested in it.”

Mr. Hersh suggested Rolling Stone, and Mr. Walsh provided a copy of the article to its editors. Not long after, Mr. Rosenthal learned that another copy had been leaked to More, a magazine that covered the media.

Now Mr. Rosenthal was apoplectic. According to More, he ordered an investigation into how the magazine got the article, which to this day is unclear. (It never appeared in print anywhere but is included with Mr. Rosenthal’s papers.)

He also fired Mr. Walsh.

“The harm to The Times and journalism is that you deliberately sent this story to another publication,” Mr. Rosenthal wrote in the termination letter, in 1974.

Brit Hume, the Fox News political analyst who was then the Washington editor of More, published a long article about the palace intrigue. He speculated that Mr. Rosenthal’s decision not to publish Mr. Walsh’s article was influenced by executives from Cowles Communications, which owned Look and was a major shareholder in The Times.

Mr. Rosenthal made no mention of Cowles in his letter to Mr. Walsh or in a memo to the Times publisher, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger.

“I have decided not to print the piece,” he wrote to Mr. Sulzberger, “simply because as it stands I do not think it is a story that carries the Alioto affair further enough journalistically.” He added, “Incidentally, I am totally satisfied as to the accuracy of the statements in the story.”

Denny Jay Walsh was born on Nov. 23, 1935, in Omaha. His father, Gerald Walsh, was an auto mechanic. His mother, Muriel (Morton) Walsh, was a beautician.

Growing up in Kansas, Denny worked at a movie theater running the projector. One film he showed was “The Turning Point” (1952), starring William Holden as a reporter who took on corrupt public officials, and in that character Denny saw a future version of himself.

He enrolled at the University of Missouri in 1954, but dropped out to join the Marines. He returned to school in 1958, majoring in journalism, and graduated in 1962.

After The Times fired him, Mr. Walsh ran an investigative reporting team for the McClatchy newspaper chain. In 1983, at The Sacramento Bee, one of the company’s papers, his investigation of a casino co-owned by Paul Laxalt, a former U.S. Senator from Nevada, resulted in another libel suit. Mr. Laxalt later dropped the case.

Mr. Walsh married Angela Sharp in 1960. They divorced in 1964. He married Peggy Moore in 1966, and she died in 2023. In addition to his daughter, he is survived by a son, Sean, and seven grandchildren.

Mr. Walsh wore down his editors in Sacramento, too.

“There I was in early 1991,” he said at his retirement in 2016. “Fifty‐five years old, unable to afford retirement, and no longer wanted at The Bee.”

He said he had been deemed a “disruptive presence.” His editors assigned him to cover the federal court. He stayed on the beat for 25 years. He was a beloved figure around the court, especially among judges.

Chief U.S. District Judge Kimberly J. Mueller told The Bee, “I would have lunch with Denny periodically to find out what was really happening here.”

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.