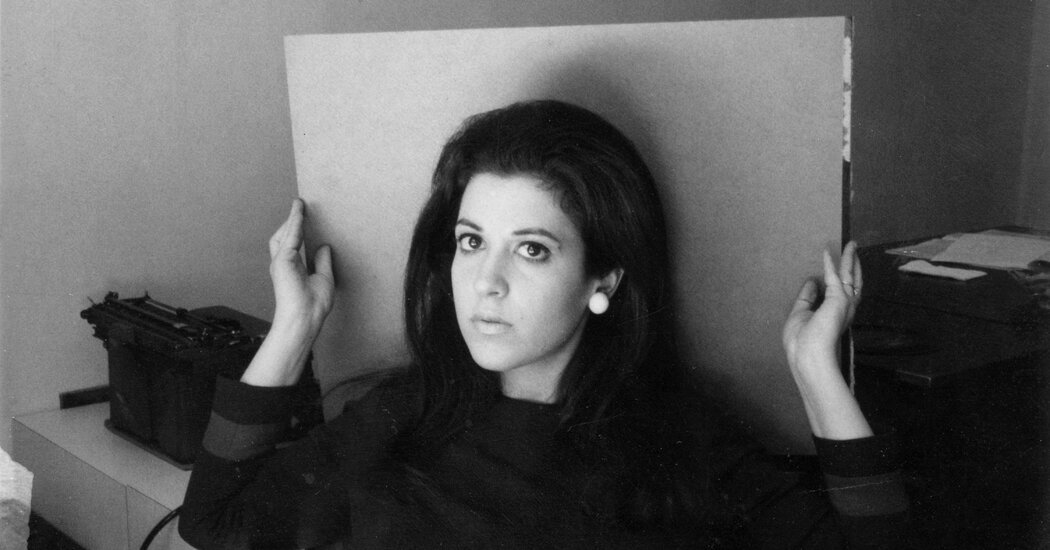

Ilon Specht, who rebelled against her patriarchal male colleagues at an advertising agency by writing a successful TV commercial for L’Oréal’s Preference hair color product that included a message of feminist empowerment that has endured for decades, died on April 20 at her son’s home in Barrington, R.I., near Providence. She was 81.

Her son, Brady Case, said the cause was complications of endometrial cancer.

It was 1973. Ms. Specht was a copywriter at the McCann-Erickson (now McCann) agency in Manhattan. L’Oréal was using Preference, a relatively new product, to challenge the market dominance of Clairol’s Nice ‘n Easy. The agency’s team had a month to create a campaign to replace one that had been canceled.

“We were sitting in this big office and everyone was discussing what the ad should be,” Ms. Specht told Malcolm Gladwell of The New Yorker in 1999. “They wanted to do something with a woman sitting by a window and the wind blowing through the curtains. You know, one of those fake places with big glamorous curtains. The woman was a complete object. I don’t even think she spoke. They just didn’t get it.”

“They” were the men who wanted a traditional ad, whose expectations she spurned. Cursing to herself in anger, she wrote the commercial in about five minutes.

“I use the most expensive hair color in the world,” the ad began. “Preference by L’Oréal. It’s not that I care about money. It’s that I care about my hair. It’s not just the color. I expect great color. What’s worth more to me is the way my hair feels. Smooth and silky but with body. It feels good against my neck. Actually, I don’t mind spending more for L’Oréal.”

Ms. Specht recited those words from memory when she was interviewed by The New Yorker. Then she arrived at the tagline.

“‘Because I’m’ — and here Specht took her fist and struck her chest — ‘worth it,’” Mr. Gladwell wrote.

But while the campaign was approved, two versions of it were shot: the one that Ms. Specht became known for, and a second, pushed by her male colleagues, in which her words were rewritten and delivered by a man as he strolls in a meadow with a woman who looks adoringly at him. She stays silent save for a giggle.

“Actually, she doesn’t mind spending more for L’Oréal,” he says, “because she’s worth it.”

That version (which never ran) was all wrong, Ms. Specht said in a forthcoming short documentary, “The Final Copy of Ilon Specht,” directed by Ben Proudfoot.

“This was not for men,” she said, “but for women and for other human beings.”

“I’m worth it” has been used, and tweaked (as “You’re worth it” and “We’re worth it”) for decades in ads and branding by L’Oréal. The first person to say the words in a commercial was Joanne Dusseau, a model and actress, then, among others, Cybill Shepherd, Meredith Baxter, Kate Winslet, Andie MacDowell, Gwen Stefani and Beyoncé.

“‘I’m worth it,’” Ms. Winslet said in a L’Oréal promotional video in 2022. “It feels pretty good to say it. ‘I’m worth it.’ It’s magic, that phrase.”

In a full-page ad that ran on May 5 in The New York Times’s Style section, L’Oréal Paris and McCann Worldgroup paid tribute to Ms. Specht.

“Her powerful words challenged the beauty industry’s standards from the inside,” it said, in part, “and inspired women to recognize their inherent value.”

Illene Joy Specht was born on April 19, 1943, in Brooklyn. Her father, Sanford, owned a furniture store. Her mother, Annette (Jacobs) Specht, worked with him. Illene started college at age 16 at Syracuse University, then transferred to U.C.L.A. when her family moved to Los Angeles. She was expelled, along with her roommate, after her roommate’s boyfriend was found in their dorm room.

She was still a teenager when she began working in advertising, first as a secretary, then as a copywriter. By then, she had changed her name to Ilon, a kind of rebranding, her son said. She worked at agencies like Young & Rubicam and Jack Tinker & Partners and was eventually hired at McCann-Erickson, where she had been a short time before she started working on the L’Oréal ad.

“She had a great deal of personal integrity,” said Michael Sennott, an account executive at McCann-Erickson who worked with Ms. Specht on the L’Oréal campaign, in a phone interview. He added, “Either you have writers who can mimic the current trend or the current trend is who they are. She really represented what was going on in society, particularly with women.”

She left around 1974 for Jordan McGrath Case & Partners.

As creative director for the agency, she oversaw campaigns for clients like Life cereal (one ad, featuring several children, included the phrase, “Unless they’re weird, your kids will eat it”) and Underalls, the pantyhose brand, which promised women no panty line, and had a tagline that said that, “they make me look like I’m not wearin’ nothin.’”

She rose to executive vice president and executive creative director but left in 2000 after the agency was acquired by Havas Advertising.

“She wasn’t part of the group that engineered the sale and saw it as a betrayal,” Mr. Case said in a phone interview.

She opened an antiques store in Ojai, Calif., but held onto her apartment at The Dakota in Manhattan, which she had purchased in 1976.

In addition to her son, Ms. Specht is survived by a stepdaughter, Alison Case; two stepsons, Timothy and Christopher Case; two grandchildren; and a sister, Meredith Schiller. Her marriages to Burton Blum and Eugene Case, a founder of Jordan McGrath Case, ended in divorce.

In “The Final Copy of Ilon Specht” — which tells the dual stories of the L’Oréal ad and Ms. Specht’s loving relationship with her stepdaughter — Ms. Specht is shown in a bed, debilitated by her illness, as she talked about the message of her commercial.

“It’s about humans, it’s not about advertising,” she said. “It’s about caring for people. Because we’re all worth it or no one is worth it.”