This article is part of Overlooked, a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times.

When Charles Darrow, an unemployed salesman in Philadelphia, learned about a new board game that was becoming popular in small circles, he asked his friends to type up the rules and help him jazz up the graphic design. In 1933, he copyrighted the game, Monopoly, as his own invention and began selling it in toy stores and department stores.

The real-estate trading game would go on to sell more than 275 million copies, has been licensed in hundreds of spinoff editions and has become part of the fabric of American life. It also made Darrow a millionaire. But credit for the idea behind it should not have been his. Rather, it belonged to a woman from Illinois with a versatile résumé that included writing, acting, engineering and working as a stenographer: Lizzie Magie.

The premise of Magie’s game, originally called The Landlord’s Game, would be familiar to anyone who has played Monopoly: People move their tokens around the perimeter of a square board, buying real estate along the way, which they can use to charge rent to other players. Magie patented her invention in 1904 — the same day that the Wright brothers filed one for their airplane — and it was published in 1906 through the Economic Game Company, a business she co-owned.

In her patent application, Magie wrote, “Each time a player goes around the board he is supposed to have performed so much labor upon Mother Earth, for which after passing the beginning-point he receives his wages, one hundred dollars.”

Magie designed the game with two sets of rules: one that rewarded the players when resources were shared equally, and another where the winner was the land baron who acquired the most wealth. Either way, she hoped that players would think about the underpinnings of capitalist society.

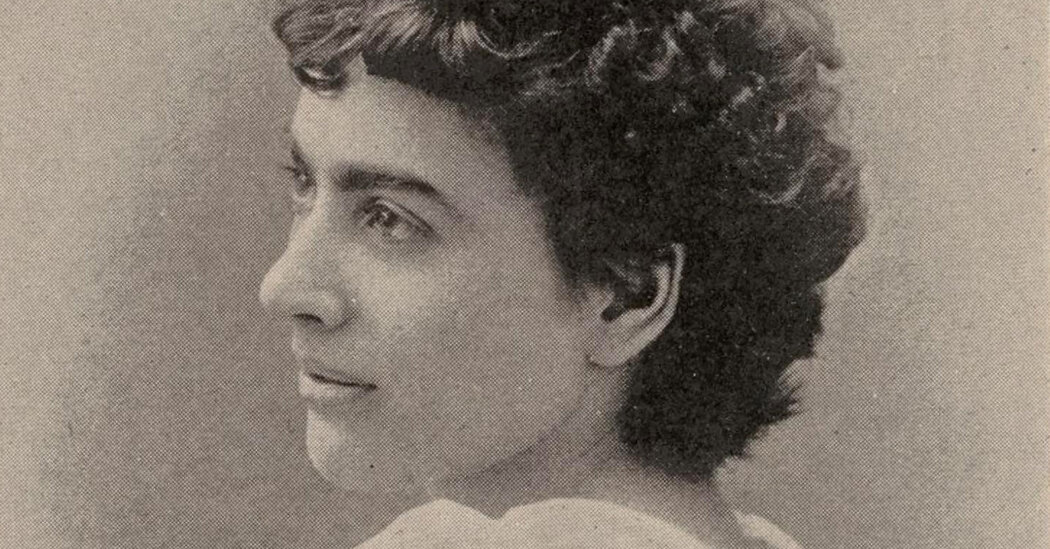

Elizabeth Jones Magie was born on May 9, 1866, in Macomb, Ill., to a political family. According to Mary Pilon’s 2015 book, “The Monopolists,” her father, James Magie, was an abolitionist newspaper publisher who reported on the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates. Her mother was Mary (Ritchie) Magie.

At various points, Magie was a poet; a stenographer at the Dead Letter Office, where mail considered undeliverable landed; a comedic stage actress; an engineer who invented and patented a device that improved the flow of paper in typewriters; and a fiction writer. Her short story “The Theft of a Brain,” published in Godey’s, a women’s magazine, was about a writer who finds success after unlocking her potential under hypnosis only to discover that her hypnotist had plagiarized her novel.

Magie conceived of The Landlord’s Game as an ideological tool: a game that would teach people about the principles of the political economist Henry George. The central tenet of Georgism was that people should keep all that they earned, but that the government should be funded by a tax on real estate owners, since land rightly belonged to everyone. A society funded by a single land tax, George believed, would eliminate both lower-class poverty and industrial cartels.

In the rules of The Landlord’s Game, Magie explained how potential conflicts could be resolved: “Should any emergency arise which is not covered by the rules of the game, the players must settle the matter between themselves; but if a player absolutely refuses to obey the rules as above set forth he must go to jail and remain there until he throws a double or pays his fine.”

The Landlord’s Game wasn’t a blockbuster hit, but it developed pockets of fans, including utopian Quakers in Delaware and fraternity brothers at Williams College in Massachusetts; the game was even adapted for the British market under the name “Brer Fox an’ Brer Rabbit.”

It wasn’t Magie’s only creation: She made several card games, including a role-playing one called Mock Trial, which she sold to Parker Brothers in 1910. That year, she also tried to sell them The Landlord’s Game, but the company deemed it too complex.

By then, she had also received some national attention for a publicity stunt she had performed in 1906, when she placed a newspaper advertisement offering herself for sale as a “young woman American slave,” with “large gray-green eyes, full, passionate lips; splendid teeth: not beautiful, but very attractive,” and describing herself as “honest, just; poetical, philosophical.”

The ad was meant to be a commentary on slavery and the bleak economic prospects of single women, but it instead led to unwanted marriage proposals and an offer of employment with a freak show. (Magie ultimately did get married, at the age of 44, to Albert Phillips, a businessman.) It also led to correspondence with the muckraking writer Upton Sinclair and work as a newspaper reporter.

In the meantime, players were converting The Landlord’s Game into homemade sets, copying the board onto wood or cloth, tweaking the rules and calling it “the monopoly game.” When devotees taught friends how to play, newcomers had no idea that the handmade game was Magie’s invention.

Monopoly’s ties to Magie were further lost to history when Darrow sold his version to Parker Brothers in 1935, claiming that he had invented it to entertain his family during the Great Depression and that he had given its properties the names of locations in the thriving beach resort of Atlantic City. A plutocratic fantasy was exactly what Americans wanted during that era. Millions of copies were sold, saving a then-struggling Parker Brothers from bankruptcy and making Darrow a rich man.

Many successful games, including Tiddlywinks and Battleship, were created as commercial versions of homespun diversions, but if a game is in the public domain, any publisher can print their own version.

Looking to squash potential competition and establish a Monopoly monopoly, Parker Brothers acquired similar games The Landlord’s Game and spinoffs like Finance.

Magie sold the rights to The Landlord’s Game to Parker Brothers for a flat $500, about $11,000 today; the firm also agreed to publish two of her other board games, King’s Men, a tile-matching game, and Bargain Day, a shopping game. Delighted that her Georgist ideas would reach a wider audience, she wrote a letter to Parker Brothers in which she addressed The Landlord’s Game as if it were a person: “Farewell, my beloved brainchild. I regretfully part with you, but I am giving you to another who will be able to do more for you than I have done.”

Although Parker Brothers, which Hasbro bought in 1991, reprinted The Landlord’s Game, it soon fell out of print again, eclipsed by Monopoly. Magie had no claim on royalties, and Parker Brothers promoted Darrow as Monopoly’s sole inventor.

Magie’s landmark contributions to American culture and game design were expunged until the 1970s, when Ralph Anspach, the inventor of a game called Anti-Monopoly, unearthed her work during a legal battle over trademark infringement with Parker Brothers.

Magie died at 81 on March 2, 1948, in Staunton, Va., but she lived long enough to see the enduring success of a game based on her own invention, even if her name had been erased and her ideology toned down.

The Evening Star newspaper of Washington, D.C., which had interviewed Magie in 1936, summarized her view: “If the subtle propaganda for the single tax idea works around to the minds of the thousands who now shake the dice and buy and sell over the ‘Monopoly’ board, she feels the whole business will not have been in vain.”