Turo, a car rental start-up in San Francisco, has been trying to go public since 2021. But a volatile stock market in early 2022 delayed its listing. Since then, the company has waited for the right moment.

Last week, Turo pulled its listing entirely. “Now is not the right time,” Andre Haddad, the company’s chief executive, said in a statement.

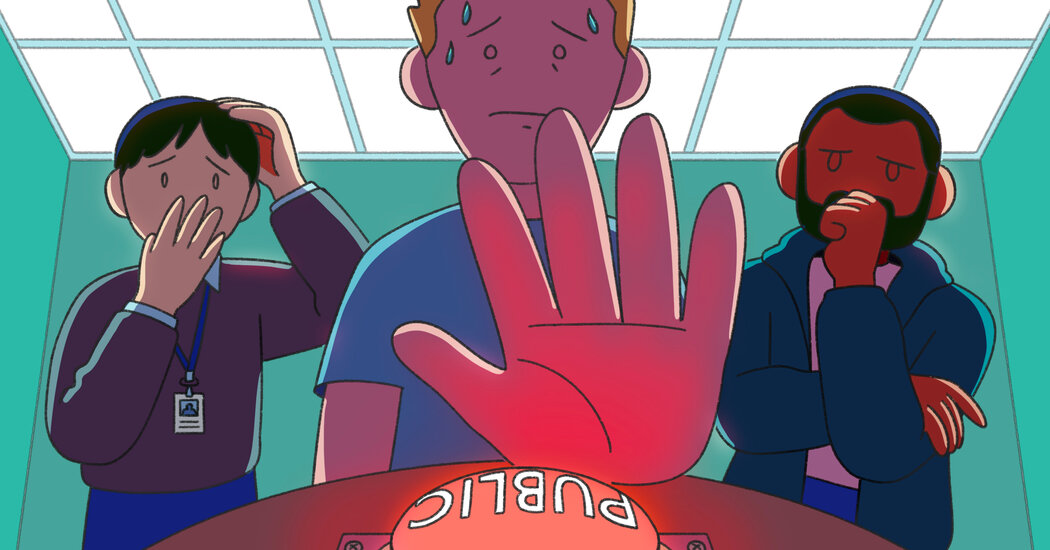

For months, investors have eagerly anticipated a wave of initial public offerings, spurred by President Trump’s new administration. Since his election victory in November, which ended a tumultuous campaign season, Corporate America and Wall Street have heralded the start of a pro-business, anti-regulation period. The stock market soared ahead of an expected bonanza of deal making.

But the administration’s tariff announcements and rapid-fire regulatory changes have created uncertainty and volatility. Worsening inflation has set off market jitters. And the emergence of the Chinese artificial intelligence app DeepSeek last month caused investors to question their optimistic bets on U.S. tech, leading to a drastic sell-off among A.I.-related stocks.

All that has affected initial public offerings. “The calendar just went from fully booked to being wide open in a span of like three weeks,” said Phil Haslett, a founder of EquityZen, a site that helps private companies and their employees sell their stock.

So far this year, the pace of public offerings is ahead of last year’s, with companies raising $6.6 billion from listings, up 14 percent compared with this time last year, according to Renaissance Capital, which manages I.P.O.-focused exchange traded funds.

Yet there are no signs of the I.P.O. wave that many had anticipated, especially from big-name companies that had spent the past two years waiting to go public. Apart from Turo’s canceled listing, Cerebras, an A.I. chip company that filed its investment prospectus this past fall, has also delayed plans to go public.

It is too early to know if macroeconomic concerns about inflation, interest rates and geopolitical risks will cause other companies to change their plans, I.P.O. advisers and analysts said. More listings are expected in the second half of the year.

“We do need to allow a little more time to see where the administration starts to land on some of these key topics that are driving some of the uncertainty,” said Rachel Gerring, the I.P.O. leader for Americas at EY, an accounting and professional services firm. “I.P.O. planning is still very much occurring.”

Klarna, a lending start-up, and eToro, an investment and trading provider, have confidentially filed to list their shares in recent months. But many of the most valuable private tech companies, including Stripe and Databricks, have indicated that they plan to stay private for now by raising capital from the private market instead.

David Solomon, the chief executive of Goldman Sachs, said last month that one reason I.P.O. activity had been slow was that start-ups could get the capital they needed from private investors. Goldman helped Stripe, the payments start-up valued at $70 billion, raise billions of dollars last year, he said.

“That’s a company that never would have been a private company today, given their capital needs, but today you can,” he said at a conference organized by Cisco.

To further ease the pressure to go public, Stripe has let its employees and shareholders sell some of their stock on a regular basis for the past few years, allowing them to cash out so they do not pressure the company to list. The transactions, known as tender offers, also resolve the problem of employee shares expiring and help workers pay tax bills related to the sales.

The number and size of tender offerings grew in 2024, according to Carta, a site that helps start-ups manage their shareholders. Carta’s customers did 77 tender offers in 2024, up from 68 in 2023. They raised $3.5 billion last year, more than double the $1.7 billion raised in 2023.

Databricks, an A.I. data company, raised $10 billion from investors in December. Part of the money went toward operations, but Databricks said some of it would also be used to let current and former employees cash out and pay their taxes.

Also in December, Veeam, a data company, said it raised $2 billion in funding that went to existing investors. This year, Plaid hired Goldman Sachs to raise up to $400 million in a tender offer that would allow shareholders to cash out, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Mr. Solomon said he has often told start-up founders there are three reasons to go public, and two of them — raising money and letting shareholders sell their stock — have been solved by the private markets.

He advised founders to go public “with great caution,” since doing so will change the way they run their businesses. “It’s not fun being a public company,” he said.

Companies that want to go public have been waiting. Many postponed their plans in early 2022 when interest rates rose and the war in Ukraine rattled markets.

Justworks, a payroll and benefits software provider, was days away from pitching public investors about a listing in January 2022 when it decided to delay. Mike Seckler, the chief operating officer at the time, said it was tempting to push through and list the shares anyway, since so much work had gone into preparing for a public offering.

But as 2022 wore on, the market volatility and poor performance of companies that listed proved Justworks made the right call, he said. Justworks did not need the capital — it had $125 million in the bank — and it was profitable.

“It started to feel like we’d be forcing something, as opposed to capitalizing on a moment of great enthusiasm for our business,” said Mr. Seckler, who became chief executive in late 2022.

Justworks eventually scrapped its listing plans and does not plan to try again anytime soon. “Our time will come,” Mr. Seckler said.

Navan, a travel and expense management software maker, confidentially filed to go public in 2022 but later pulled its plans, a person familiar with the matter said. The start-up recently went on a “non-deal” roadshow to meet investors and lay the groundwork for a listing in the second half of the year, the person said.

StubHub, the ticketing company, which filed to go public in 2022, is also aiming to list its shares sometime this year, a person familiar with the matter said.

With the volatile market, bankers have pushed tech companies, which are often unprofitable, to find a way to make money, people familiar with the conversations said. Bankers want start-ups to generate at least $200 million in annual revenue to appeal to public investors. If a company is smaller or losing money, investors want to see high revenue growth, the people said.

“The bar went up for the type of companies that can be public,” said Amy Butte, Navan’s chief financial officer.

Sanjay Dhawan, the chief executive of SymphonyAI, a software company, said bankers have told him to hit $200 million to $300 million in revenue before going public. The company surpassed $400 million last year and turned a profit, he said.

Mr. Dhawan added that he had been waiting for clarity from the election before making I.P.O. plans.

“Now everyone knows what the economic policies will look like,” he said. “Everyone is feeling a bit relieved to start planning.” The volatility from DeepSeek was only a short-term reaction, he added.

At least one tech company recently made it to the public markets. On Thursday, SailPoint Technologies, a cybersecurity company backed by the private equity firm Thoma Bravo, raised $1.38 billion in a public offering that valued it at around $12 billion. But its stock fell 4 percent below its I.P.O. price of $23 a share on its first day of trading.

For the public offering market to really get going, “it’s going to take a few brave companies to come out,” Mr. Haslett of EquityZen said.